A brightly painted wooden doll, demure faced, dressed in a long, shapeless gown was what my brother Abu brought back for me from Russia. As Deputy Director General of Malaysia’s Fisheries Department of the Ministry of Agriculture, he’d spent two months there as Malaysia’s representative to the Group Fellowship Study Tour.

I’d never had a doll like that. It produced, as if by sleight of hand, six other similar dolls, each decreasing in size. The last was a little bitty baby. Seven dolls in one! All six dolls could be neatly nested back into their mother. How I cherished my bewitching babushka doll.

One night we found Mother’s outdoor laundry tub crawling with prawns. Abu wanted to study their breeding habits. Then a gigantic salt-water aquarium with a dazzling variety of marine fish appeared in our house. Eyes shining, Abu recounted their names and habits to my kid sister Faridah and I.

Abu took us by surprise in many ways. He built a cabinet to house Mother’s battered treadle Singer sewing machine. The rich gleam of its polished wood matched the glow on her face when she saw it. He then delighted her by giving her rusty old Frigidaire refrigerator a shiny new coat of paint. Little did I expect his talents to include designing fine jewelry. He crafted an elegant tiara with glittery rows of gemstones which I proudly wore for my wedding.

Abu fixed faulty doors, loose hinges and electrical fittings gone awry. I recall my husband Samad feeling dejected having smashed his speedboat’s perspex front screen when mooring it at the Port Klang Yacht Club. Abu quickly had a new screen installed.

Abu married Azizah, the granddaughter of a wealthy Arab from Hadramaut, Yemen, a charming, bright-eyed girl with thick wavy hair and a fair complexion which was much admired. Her grandmother, Tok Bibi, was Mother’s first cousin. Azizah’s family affectionately called her Chik, short for Kechik meaning “little one”.

For weeks Abu toiled in his workshop at the back of his house building a decorative lamp for his new bride. Its slim neck was joined to a bulbous body made of a lustrous metallic substance. It glowed cheerfully in a corner of their living room.You are the only one owning such a lamp, he teased her with a smile.

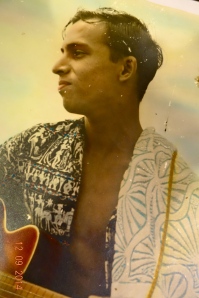

In addition to playing the piano Abu loved strumming his acoustic guitar or plucking it with a plectrum which he did with great skill and dexterity. Chik was taken aback when he built a Hawaiian guitar. He would lay it flat on his lap to play it, moving a steel bar up and down. As his technique improved he produced wondrously smooth glissando effects. Chik told me his “Rhapsody in Blue” was unforgettable.

Ten years after they were married, a beautiful boy they named Azmil arrived. Abu doted on his son. When he turned four, Abu would sit him on the piano stool and show him how to move his tiny fingers on the keys. Azmil had inherited his father’s musical talent. He learned fast. Abu taught his son to fly radio-controlled planes, placing the radio transmitter in his tiny hand. Azmil whooped with joy whenever he got a plane to circle overhead. He crashed many planes but Abu lovingly restored each one of them.

He astonished Chik yet again when he announced his intention of building an electronic organ. It was hugely more challenging than making a Hawaiian guitar but Abu persevered. He scoured the music shops and began collecting parts for it. When he attended a six-month course on the Fundamentals of Electronic Engineering at the International Center for Advanced Vocational Training in Turin, Italy, he found most of what he needed and returned home to work on it in earnest. He meticulously put together piece by intricate piece and integrated all the required features including tone generation, amplification, loud speakers, pedal board and a host of other features. I recall it resembled an upright piano but Abu produced an intricate pattern of sounds from it. He was a one-man band.

When Abu was required to attend a meeting in Manila, Chik got his clothes ready. She brushed his jacket and laid out the shirt and tie he would wear on the plane.

Two days before he was scheduled to take off, his boss, Ungku Ubaidilah, Director General of Fisheries requested that Abu meet the Minister of Agriculture, Dato’ Ali Haji Ahmad in Penang and accompany him to Kuala Lumpur as he was unable to do it himself. So Abu flew to Penang instead.

On December 4, 1977, shortly before boarding his plane in Penang, Abu called Chik to say he’d be back early that night. He chatted with Azmil and affectionately wished him goodnight. Malaysia Airlines or MAS’s flight MH 653 with 97 passengers and 7 crew members left Penang at 7.21pm for Kuala Lumpur. According to what was later revealed, as it started its descent at Kuala Lumpur’s Subang airport, the captain G K Ganjoor reported an “unidentified hijacker” on board. Minutes after that he radioed, “We are now proceeding to Singapore”. But they never reached Singapore. A series of gunshots were heard in the last few minutes of the cockpit voice recorder. The plane went down in the swampy ground at Tanjong Kupang in Johore at 8.36pm. It was a burning wreckage. There were no survivors.

It was MAS’s first fatal air crash. The circumstances in which the hijacking and the crash occurred remain unsolved.

In the dead of night my cousin Ahmad Merican, MAS’s Public Affairs Manager, called us with the tragic news. The unthinkable had happened. Our beloved Abu, Mother’s darling son was no more. But the news made no sense to us. It took a while for us to absorb it. Our thoughts went to Chik and seven-year-old Azmil who in an instant had become fatherless. How to break the news to them?

We were to learn later that Azmil had been fretful that night, crying ceaselessly and refusing to go to bed. Chik took him upstairs and stayed with him until he slept. Tired herself with questions about Abu’s delayed plane running through her mind, she fell asleep too.

At 5am that morning Father, my sister Faridah and I rang Chik’s doorbell. She greeted us sleepily but her usual bright smile instantly faded when she heard what had happened. We thought she bore the news remarkably well but we knew she was numb with shock. The pain and grief would come later. We took turns to hug her.

A few weeks after the crash, Father, Chik, Azmil and I flew to Tanjong Kupang and joined the other bereaved families for the mass funeral. The dismembered parts of the victims had been collected and placed in seven coffins draped with white cloth. The tears flowed freely. It was too much for Chik to bear. A doctor sedated her and led her to a room to rest.

She was later taken to the nearby police station. There among the tattered personal effects of the victims she recovered Abu’s mud-spattered wallet with his smiling photo inside.

Chik suffered terribly. Is there an end to such grief? But she learned to cope with her pain and anguish over the years.

More recently MAS has had two further air disasters. MH 370 was thought to have disappeared over the Indian Ocean on March 8 this year. A few months after that, on July 8, MH 17 was shot down over the Ukraine. The tragedies have caused great sorrow to the relatives and friends of the victims. The families of the passengers of MH 370 have waited six months for answers as they know nothing about how the plane disappeared or where it landed. But Chik and the other loved ones of those who had boarded MH 653 have been waiting for answers for 37 years.

(I ATTACH AN ARTICLE WRITTEN BY ABU’S CLOSE FRIEND RAJA ISKANDAR BIN RAJA MOHD ZAHID)

ABU BAKAR MERICAN

When I entered the University of Malaya (UM), then in Singapore, as a freshman in October 1953, Abu Bakar Merican bin Basha Merican, known to me later as “Bakar” and to most members of his family as “Abu” and even only as “Uu”, was already a second year engineering student there. As was then customary in UM, a freshman was a victim of “ragging” by the senior students for a few weeks as a “freshie”. When I first arrived by taxi at about 5 p.m. at the UM hostel compound at Dunearn Road, my hostel block, I learned later, was just opposite Bakar’s block. I was lucky because there were no seniors around at the time. There was only the house-keeper who gave me the key of my hostel room.

When I entered my room I found that the other occupant was Osman Sham who was with me at the Malay College in Kuala Kangsar (MCKK) doing a Form VI course to enter the UM. He warned me that to go out of our room as a “freshie” we had to wear a necktie and “obey orders” given by the “seniors” as long as the orders were humane. We were not to give in to orders that were not respectful like being asked to strip naked. Ragging would go on for just about three weeks, he told me, so it was quite alright to enjoy university life and behave like a humble “freshie”.

Once I was out of my room I was first met by a senior who, noticing my necktie, started asking questions in a boss-like manner and finally asked me to do a floor-dipping exercise as many times as possible. It was an exercise I was regularly doing so that was no problem at all. But it was when other seniors arrived at the scene and started to order me to do more floor-dips that a Malay senior came by and pulled me away from the crowd under the pretence of wanting to ask me to carry some bags for him. He brought me to the opposite side of my block to his room. It was then that I learnt that his name was Abu Bakar Merican. He asked me to call him just “Bakar” and not “Senior Gentleman” like I was asked to call the other seniors. In his room there was a guitar with an electric guitar pickup and a home-made hawaiian guitar. I knew right away that he was a musician.

Having won the first prize in a singing competition at MCKK as a Form Vl student in1952, it took little time for me and Bakar to start a musical session in his room. This session drew a small crowd which included another freshie, Zainuddin Hashim, who was another MCKK Form VI student who entered the UM together with me. Zainuddin had a voice like Bing Crosby which made me call him “Bingo”. Bingo played the guitar and became my partner in duet singing at MCKK. We used to sing duets together in Bakar’s room and at freshies’ night performances at the hostel block enclosure. At the end of the freshies ragging period we also sang together on the UM stage. We first sang “South Of The Border” which was really liked by the audience of seniors. After applauding our singing they asked for more. We were then invited to join the UM Choir Group by the choir leader, under the choir orchestra bandleader Paul Abisheganaden.

While enjoying musical sessions and being close to Bakar during my first year at UM, I noticed that he was also interested in constructing electronic gadgets like making audio amplifiers and radio sets. He had a radio set he had made with its audio enlarged by an audio amplifier which he had also made himself in his hostel room. This was in addition to the hawaiian guitar I mentioned earlier which needed the audio amplifier for a loud sound amplification. He told me he had also made a car radio set for his father in Penang. This interested me because although I attended the arts course at UM, my personal interest was in electrical things except that I did not know how to go about learning or constructing anything electrical and electronic.

One day I passed by the workshop room of the Engineering Department. On its notice board I saw, “Learn How To Construct Your Own Radio”. A date was given and since it fell on a Saturday afternoon I was able to attend the session.To my surprise it was conducted by the Radio Club of the Engineering Department whose President then was Teoh Chye Poh. It’s Secretary was Abu Bakar Merican. I paid $9.00 for the electronic parts needed to construct a one-valve regenerative radio set and listened to the instructions given by Chye Poh and Bakar on the proper way to wind the coil and how to solder the various electronic parts together. That was how I learnt to read an electronic diagram and to know the various names of the electronic components that would be beyond most arts students.

During the final term holidays that soon followed, I soldered the various parts of the one-valve regenerative radio set at home. Unfortunately it did not work. Disappointed I went to the Dunearn Road hostel, knowing that Bakar was not going back to Penang for the holidays. Bakar was in his hostel room with Chye Poh and I asked them why my one-valve set did not work. They started touching the various components with the battery connected but without success. Finally Chye Poh reversed the two wires to the reception coil and to our surprise the radio worked! That proved that my first attempt at making a radio set was okay except that the reception coil was reversely connected. What I remember to this day was what Bakar said, patting me on my shoulder, “Congratulations! You have just made your own first radio set!” He was right; I was really proud of that fact!

Bakar’s neighbour’s room-mate had a book called “Radio For Boys” which was lent to me. It had many diagrams and instructions on how to construct a one-valve set, a two-valve set, a three-valve set, all run on battery power, and a simple five-valve superheterodyne (superhet) set run on electrically energised power supply. During my second year at UM my hostel room was right next to Bakar’s and with his guidance I was able to construct the various radio sets right to the superhet set. But before graduating to the construction of all these radio sets, Bakar and I found out that the one-valve regenerative set was capable of being modified to function as a simple transmitter set by increasing the level of its regenerative output. That made it a simple Morse Code transmitter by cutting on-and-off its power supply to provide the dot-and-dash function as a transmitter. In fact by inserting a carbon microphone at the input section of the one valve set, even a voice transmission was capable of being produced. Bakar and had our fun at doing a bit of two-way communication with our one-valve sets, using only short antenna lines. Transmission by using long antenna lines would be detected by the communication authority. That would have put us in trouble as it was illegal to transmit without a licence.

Unfortunately Bingo was not back at UM for the second year course as he had joined the police force as a police inspector. However, a few of the new freshies were musically inclined like Ariff Ahmad, Daud Hamzah, Philip Chee and another Abu Bakar. Together with them we formed a small music band with Bakar playing the strumming guitar, Ariff the melody guitar, Daud the big violin-shaped bass, Abu Bakar the drums, Philip Chee the piano and me the hand percussion instruments. I had won the first prize in the Radio Malaya “Bakat Baru” competition in March 1954 and was one of the singers of this group. We performed at our hostel ground and on stage for certain functions together with singers like Ahmad Sabki and the lady singers Adibah Amin and Fung Chui Lin. Once Radio Malaya even invited our group to perform at one of its “University On The Air” programs.

When we all left UM, our music group naturally broke up. I joined Radio Malaya in 1957 as a Programme Assistant and Bakar the Department of Fisheries in the Ministry of Agriculture. We seldom met. I continued with my interest in electronics, building sophisticated audio amplifiers, purchasing a professional communication radio receiver, constructing a tranmitter and a 1,000 watt transmitting amplifier after obtaining a licence in operating an amateur radio transmitting station. I managed to pass the amateur radio examination (RAE) in December 1961, getting a call sign 9M2RI. I tried to encourage Bakar to be involved in it too, but he was not interested in the hobby.

Meanwhile Ariff Ahmad and Daud Hamzah joined me at Radio Malaya as Broadcasting Assistants. Ariff joined the University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur and later took up a university course in music. He obtained a PhD degree from an American University. Unfortunately he passed away, after Daud Hamzah and Abu Bakar, the drummer of our UM music group had passed on. Philip Chee was in Singapore and was out of touch with us in Kuala Lumpur.

While in Kuala Lumpur, I once visited Bakar’s house. I discovered that his activities in the Fisheries Department had made him interested in keeping an aquarium of marine fish which was more difficult to maintain than keeping a fresh water aquarium. I learned a lot from him about the problems involved and soon built my own marine aquarium, getting marine fish and the seawater and sand from the 4th mile in Port Dickson. I even caught a baby octopus, which was not tame at first, but soon began to be friendly once I learned to feed it by dangling a dead prawn in front of it.

Another influence Bakar had on me was in the area of constructing musical instruments. He had made a hawaiian guitar for himself and for his colleague, Dol Ramli, who later became the Director of Broadcasting in Malaysia. One of my sons was interested in playing the modern bass electric guitar and had asked me to buy one for himself. I decided to construct one instead of buying it for about RM700. I purchased only the commercial fingering section for RM150 but constructed the body and the electrical sound control unit by myself. When it was completed, I gave it to my son who enjoyed playing it with his friends. I then went further to build an electric guitar on the same principle of buying the fingering section for RM150 and building the body like those sold in the shops and building the electrical sound system myself. After this was successfully completed I was encouraged to build another electric guitar, a simple one with a very light body just big enough to fit in the electrical sound system on it.

I then went even further. Being interested in playing the violin as a 10 year old kid, I had much earlier on made a violin using the coconut shell as the violin’s sound box and the fibres of the pineapple leaf, instead of a horse’s tail hair, for the bow of the violin. With new knowledge in building the bass guitar and the two electrical guitars, I decided to build an electric violin without the normal big sound box needed to produce the musical sound. The sound box was made from a small piece of hard wood to fit in the electrical parts for the string sound pick-up, and the fingering board was another piece of hard wood with the string tuning system at its edge fitted with the metal tuning gears used for the mandolin. This violin was very much like the one used by a famous violinist, Vanessa Mae. Vanessa used it around the year 1995, but I made mine in 1985.

Not satisfied with just this violin, I made another simpler electric violin, using just one piece of hard wood as its fingering section, right from one tip as the string tuning section, to the other end where the four strings GDAE were attached. The only other piece of hard wood used was for the small, almost round, board needed to hold the violin to the player’s chin and shoulder. This made the electric violin look like just a small piece of wood with four strings attached to it. It was therefore very simple to carry around without the need for a violin box. Every one stared at this funny looking violin whenever I brought it with me under my armpit!

News of the deaths of many of my friends, including some members of my close and distant families, somehow did not affect me very much as I always had the feeling that they were being recalled by God’s grace. But when the news came on radio and TV that a commercial aeroplane crashed in Johor in 1977 killing all of its passengers and crew members, my eyes were really full of tears. This was because one of its passengers was Abu Bakar Merican.